Two days after South Carolina seceded from the United States on December 20, 1860, with 10 more states following suit, fresh stacks of the Grand Rapids' newspaper, the Daily Eagle, lay along with streets with an enlistment call from President Lincoln in the headlines. He needed 75,000 troops to serve for three months. When Confederate troops opened fire on the Union garrison in Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, neither side predicted how massive a conflict this minor scuffle would become.

The very next day, December 23, 1860, concerned citizens of Grand Rapids attended a meeting at Luce’s Hall, where the Grand Rapids Art Museum now sits, chaired by city leader John Ball to discuss the incident at Fort Sumter. In the packed smoky hall there was talk of creating a regiment. A week later, at the Armory of the Valley Guards, three military companies along with a good number of Grand Rapids’ citizens met to make a decision to form a regiment. On June 10, 1861, the Third Regiment was formed, with a total of 1,040 local citizens becoming soldiers, part of the 4,214 Kent County men who would end up signing up to serve in the Civil War.

Though the Civil War was fought over slavery, African-Americans were not permitted to sign up as soldiers until after the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Some states like Massachussettes quickly changed their laws and enlisted "men of African descent" to fight. Many Black men, including some from Michigan, left to join them in the spring. Later, the First Michigan Colored Troops infantry regiment was organized in Detroit in August of 1863.

The Grand Rapids of the early 1860's was not the furniture giant it was going to be 20 years later. It would have resembled more of a frontier town complete with bordellos and saloons. That is not to say that the city was not beginning to grow in population and sophistication. It had seen its first cobblestoned roads, Monroe and Canal Streets, as well as the first four-story brick building in 1856. In 1859 the first Opera Hall was built on Canal Street, which is now Monroe Street, between Erie and Bridge, where DeVos Place now stands. Grand Rapids had only officially become a city 11 years before the Third Regiment was enlisted into service and boasted a population of no more than 10,000 citizens. Louis Campau had established his trading post on the banks of the Grand River only 35 years prior to the start of the war.

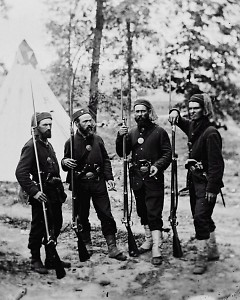

Many of the men enlisting in the Third Regiment came from a rural backgrounds with hunting and outdoor skills bred into them. These skills would come in handy when facing Robert E Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Most of the white people who lived in the Southern states at the time were rural farmers that came with skills more conducive to a soldier. This gave them an advantage on the battlefield, resulting in over 16,000 more Northern soldiers than Southern soldiers dying in combat deaths.

The Third, also made up of many rural Michiganders, in a lot of ways mimicked the Virginians or Alabamians they would soon encounter in their territory. General Phillip Kearney, Third Division commander in which the Third Brigade was attached, recognized this strength.

“Send me a Regiment,” he is reported to have said in the heat of battle during the Peninsular Campaign, before changing his order to “Send me a Michigan Regiment, quick.”

During the battle of Fair Oaks or Seven Pines- depending on what side you were on- the Third Infantry would get its first taste of heavy combat.

The effects of Fair Oaks were felt in Grand Rapids very shortly after hearing the news of the battle.

“Our poor boys!" wrote Rebecca Richmond, a 20 year old resident of the city, in her diary. "Our city is in a state of excitement and mourning and constantly expecting the dreaded confirmation of our worst fears.”

The number of graves in the Fulton Street Cemetery started to rise. One of them was a local store owner, named Captain Samuel Judd, who was leading a company when he was killed. The tall off-white obelisk is still in the Fountain Street Cemetery today. All together, the regiment lost 30 men with an additional 124 wounded and 15 missing. Although a relatively small battle in the war, the casualties produced from this one battle were over half that of the entire eight year American Revolution.

By the time of the Civil War there were 13 churches in Grand Rapids representing many denominations. The women of the Westminster Presbyterian Church took up sewing garments for soldiers while others hosted dinners in order to raise money for various items. Ministers would hold services in the two camps around the city, Anderson to the south, a training ground, and Lee on top of the largest hill in the eastern outskirts of the city, now the site of Central High School and the historic homes that surround it. Dr. Francis Cummings, a pastor of St. Marks, joined the war effort to serve as a chaplain. A year later he would meet the largest killer of the war: unsanitary quarters and lack of sterilization. He had caught tuberculosis and died on August 26, 1862.

As the war progressed, Robert E. Lee's aggressive attacks gained ground, resulting in President Abraham Lincoln removing George McClellan and replacing him with John Pope to command the Third Brigade, of which the Third Regiment from Grand Rapids was a part. Pope quickly grew to recognize their high skill level.

“The third Michigan being the only one that I could at the moment call upon," a report from Pope says. "And being one of the best, it was sent.”

Soon after the Battle of Gettysburg, a turning point in the war, the 283 men of the Third from Michigan found themselves in the middle of an open peach orchard on one of the hottest days of the year, wearing wool uniforms. Outnumbered and holding their ground, they held off the hard fighting Third South Carolina Regiment charging toward them with their screeching rebel yell. They pushed the rebels back over 300 yards to the Rose farm where heavy fighting broke out. Bullets whizzed by their heads as they stood in the open field loading and firing so fast that many rifles became overheated and useless.

The men of Grand Rapids stood their ground under heavy fire knowing that if they retreated the whole Union line could collapse. However, within an hour the troops were forced to begin retreating east. They ran as fast as they could over a mile of open ground hoping not to be shot in the back or hit by artillery. The men of the Third would end that day with 16 percent of their regiment as casualties.

After Ulysses S. Grant's promotion to Commander of all Union armies, the Third saw some of the darkest days of the fighting. On June 9, 1864, a majority of the regiment was sent back to Michigan to be discharged due to their enlistments running out- they had served the time they signed up for. The men who were left of the "Old Third" were reconsolidated into a battalion of four companies and attached to the Fifth Michigan.

Back home in Grand Rapids the war had taken a psychological and economic toll on the city. The graveyards were filling up while families tended to the wounded.

“You cannot think what feelings I had while listening to the sermon and seeing the parents mourning for their son,” Lydia Lewis wrote in a letter to her son. From March 1864 to February 1865 the price of a bushel of wheat rose 40 cents while eggs went up 15 cents. Railroad construction in the state also came to a halt during the war due to lack of iron and other equipment. In 1864 the Common Council issued bonds to provide enlistment bonuses in order to replenish the Michigan regiments. The coming and going of military personnel along with others looking for work grew the population exponentially during the war. This led to the 1864 decision to build a public transit system. It also became the second city in the state to purchase a steam fire engine.

On April 9, 1865, when Lee’s army surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, the next day the Daily Eagle came out with the headline “Babylon has Fallen!” In June of 1865 the Fifth Infantry was discharged from federal service in Detroit.

The Third Regiment had certainly been in the middle of the fray in some of the Civil War’s bloodiest battles. In the end the Great Lakes State would give almost two percent of its population to the war effort.

The men who remained of the old Third began to make their way back home. In mid-July that year veterans of the unit started returning to Grand Rapids where they were greeted as heroes. Brigadier General Byron Pierce returned to the city in July as well. Eventually he became the first commandant of the new Michigan Soldiers Home which he had worked hard to bring to the city. After leaving in 1891 he leased the Warwick Hotel, built by the cousin of Buffalo Bill, that was on Fulton and Division. On June 13, 1911 he was one of the guests of honor to unveil a monument to the units that enlisted from the city in 1861 at the old fair grounds. He lived at 47 Jefferson until his death in 1924 where he was buried at Fulton Street Cemetery.

In 1871 the first reunion of the Old Third Michigan Infantry Association was held at Sweet’s Hotel which sat on the future site of the Pantlind Hotel. This is where they would meet throughout the years as their numbers slowly dwindled, with their last meeting held in 1927. Six of the remaining fourteen were in attendance at this last meeting. It would be 10 more years before the Third would see its final member,Willard Olds, pass away on August 30, 1937 at his home in Belding, Michigan.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.