Pantlind Hotel inscription /Rachael VoorHees

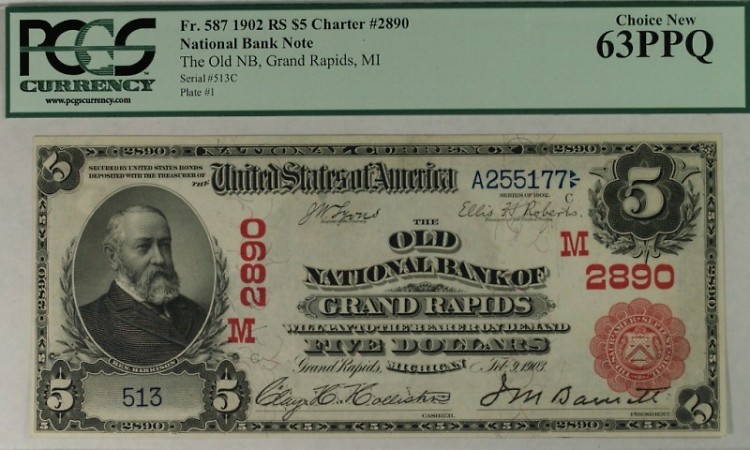

$5 Red Seal - Old National Bank of Grand Rapids /Mullen Coins

Pantlind Hotel inscription /Rachael VoorHees

Have you ever wondered what kind of money people used when they came to Michigan and settled down in what would become Grand Rapids? Generally speaking, it wasn’t dollars and cents. In fact, there was very little actual money on the frontier. After a more recognizable and universal currency was adopted in 1863 when Abraham Lincoln signed the National Banking Act into law, Grand Rapids even had its name on U.S. currency for a time.

Michigan was ushered into statehood and the Union in 1837, but the decades prior to that had seen a great deal of movement among populations. The People of the Three Fires - the Ojibwe, the Ottawa, and the Potawatomi - sided with the British in the early part of the 19th century as a way of preventing being overrun by waves of immigrants from the East. After the United States won the War of 1812, the U.S. government moved them west and onto reservations making way for Yankee resettlement from New England and upstate New York.

In 1838, the year after Michigan became a state, Grand Rapids had incorporated as a village. By the time it was incorporated as a city, in 1850, it had 2,686 people living within the city limits, according to the census. What were these people using to purchase the items they needed to live their lives? A makeshift system of coins, barter and other tools of exchange.

On the frontier, people generally did not use coins, partly because they weren’t minted and distributed within the area. The only coins they came across were ones new settlers or other travelers brought with them. In 1792, after the United States became a country, it began issuing its own currency. These were dollars and cents rather than the British pounds and shillings that had been in use in the colonies. Local currencies still held sway for a long time, though, as states and regions acted independently of the federal government. Other coins, like the Spanish piece of eight had intrinsic value because of what it was made from: silver.

For the new Village of Grand Rapids, the lack of circulating money was a problem to be solved. Louis Campau promoted a bank on Canal Street, but it closed for lack of funds. In 1838, the village trustees passed a resolution to issue $300 in one- and two-dollar shinplasters for local use. These were promissory notes that acted as private IOUs and could be exchanged for goods or services. When people needed to pay larger debts with official money, they often had to wait until friends or travelers arrived in town.

There were no functioning banks in the 1840s, but in the 1850s businessmen began forming them again. Several of these, including the bank of Revilo Wells and a branch of the Fentonville Bank closed suddenly when the owners left town with people’s deposits. In 1863 the National Banking Act was passed with the goal being to force all currency out of use except for notes that were backed by the U.S Treasury and printed by the government itself. These were the prototype “dollar bills.”

As a result of this, for awhile there were actual “Grand Rapids” dollar notes, the currency of the Old National Bank of Grand Rapids. The Old National Bank was chartered in 1883 and was the product of the previously established First National Bank and the M.L. Sweet & Co. Exchange Bank. Students of Grand Rapids history may recognize the name - the Old National Bank took new offices in the Pantlind Hotel in 1915. This building remains part of the Amway Grand Plaza today. From 1883 to 1929 this bank issued $11,877,550 worth of national currency. After 1929, of course, Grand Rapids banks had a whole host of new problems to deal with.

Five-, ten-, and twenty-dollar notes from the Old National Bank of Grand Rapids are quite collectible now, so if you’re looking for a piece of local history that will take up little space and will not need to be dusted much, there’s an idea (just in time for Christmas). According to Pat Mullen, owner of Mullen Coins, “Some collectors choose to have just one really nice note, while others work to acquire one of each denomination from each Grand Rapids bank. Both are fascinating ways to look at our past.”

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.