Most of the news coming out of Detroit for the last 50 years has been on a trajectory moving from bad to worse. From the implosion of the auto industry to reports of rampant crime, poverty, failing schools and evacuated neighborhoods, public perception is that this once great American city may be beyond recovery. Last week at the BALLE business conference, attendees at GRCC Wisner-Bottrall Applied Technology Center saw the documentary film “We Are Not Ghosts” and were given a picture of Detroit that is much sunnier than the one we have come to expect.

Melissa Young and Mark Dworkin's hopeful film focuses on the work being done by ordinary citizens in Detroit to make the city a vibrant, prosperous place to live once again. It's an underdog tale of a devastated city whose long-suffering inhabitants have decided that they are no longer going to wait around for the police or politicians to fix things. Instead, these plucky Motor City residents seem to have that distinctly American “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality of their city’s forbears, and they have taken it upon themselves to be the change that they wish to see in Detroit. It's a portrait of a regular group of people, small business owners, educators, activists, poets and musicians, that like brilliant patches of green in a concrete jungle are serving as signs that life can emerge from death.

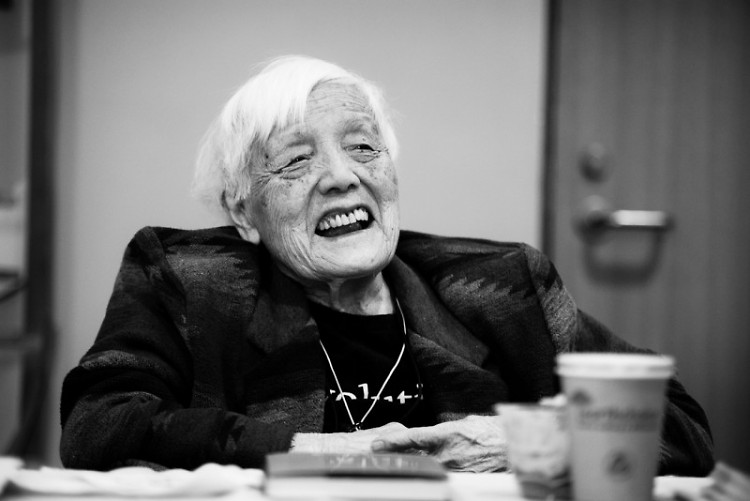

Grace Lee Boggs, lifelong champion of social justice causes along with her husband James Boggs, was at the center of the civil rights movement in Detroit. She was a subject of the film and attended the screening. At the end of the film, this tiny, frail woman with a weathered yet brightly smiling face, was brought forward in a wheelchair to the front of the room to join a small panel from Detroit there to take questions from the audience. It wasn’t until she was given the microphone that it became evident how much vitality and intelligence Boggs possesses.

The audience was in rapt attention as she spoke eloquently and commandingly about the damaging effects of urbanization and technological progress on our spirits and how in our age we have a lot of work to do to “re-grow our souls” and “become fully human” once again. Melissa Young, one of the directors of the film, said she wanted to include Boggs in the film because she empowers people who are committed to justice and equality and helps them ask the most important question, “If I don’t do it, who will?”

The Rapidian sat down with Boggs to learn more after the panel discussion.

Jonathan Stoner: Why did you move to Detroit and why did you stay?

Grace Lee Boggs: I came to help edit a newsletter and I stayed because there is such a sort of challenge about the city, it was so African-American and I’d never had that experience of living closely with African-Americans. My husband was African-American and people would come to the house like they were neighbors and they would talk freely and carry on much as they would [with] each other without my presence, and that’s so unusual. I think the way that we are separated from one another, not only by race but by age and by fear is so dehumanizing the few opportunities that we have we should grab.

JS: What inspires you about the young activists in Detroit?

GLB: Well, it’s not so much inspire… I was on the platform in New York a couple weeks ago with a young Occupy Wall Street activist and she was charming but I realize that for her and for many young people being with their peers in some sort of action is very exciting. I realize that excitement doesn’t always last. I ask myself, what is the role of those of us who are older? Do we flatter them? How much do we depend on them? Do we challenge them? [Or] do we bring them something that society has denied them, the contact with older people?

JS: What would you say to the next generation of activists?

GLB: I would tell them the story of my husband. I didn’t understand it at first, [why] he used to go around old people. He would try and find out what they needed. He would help them get this, that or the other thing. And when one of them died he would find another one to help. I didn’t realize that he was getting a great deal from that interaction. He felt a spiritual need for it and I realized then that age segregation is probably as bad or worse than race segregation. [I would tell them] how much age segregation there is today. And how [in] our society, the human race has really only evolved because there is always this interaction between the generations which has been denied by urban society.

JS: You also see the connection between the old and the young, breaking down those barriers that have separated us from each other, right?

GLB: I think the young have a limited concept of justice. They understand that people are poor and some are rich and they feel that the poor have suffered and the rich have prospered and that somehow redistribution will solve that. But justice is much more than redistribution. There’s all sorts of relationships, all sorts of institutions [and] all sorts of cultural changes have to take place. We can no longer think in terms of punitive justice only. We have to think in terms of restorative justice. And we have to ask, so what is restorative justice?

JS: Can you expand on how we are, in your words, “only beginning to understand that in the course of all this expansion we have lost our souls, we have damaged ourselves?”

GLB: [We need] to think of it as I think of it now: as that capacity to create the world anew, to believe that each of us has that capacity, that despite all the principalities and powers, we can embrace the conviction that we have the power within us to create the world anew. We live in a world where being strictly rational is the ideal. And you think it’s only the people who are sort of ignorant who have a superstition of believing in our souls, you think that was something of your childhood that you left behind. I think that belief in spirituality as something that is different from religion is really very, very important. Religion is a belief in a doctrine and it leads to all sorts of struggles and [there is] dogmatism about it. Spirituality is not a dogma. It’s not a series of truths that you embrace and try to get others to embrace. It’s something that expands you, that empowers you.

JS: What is the new American dream?

GLB: The [old] American dream was that we could keep growing and growing and growing and it would never stop. We would have more goods; we would more comfort; we would have more conveniences; technology would not contain internal contradictions. The idea that at a certain point [the American dream] could bring terror never occurred to people and yet that’s what it’s brought. I mean we’ve bought comfort and convenience at the expense of the planet, of other living things and of other peoples. Now we face the terror of global warming, of 9/11…

JS: So what’s the new American Dream then?

GLB: We need a sense of time: what time it is and what time it isn’t in the world. We have lost that sense of transition of what happens from generations to generations. We don’t need more things. We need great transformation, or what Martin Luther King called “a radical revolution of values". We need to become more fully human. To realize how much we’ve been damaged is not easy. We need to look at ourselves and how damaged we have been by the damage we have done to others. To understand the enormous cost at which we have bought our comforts, that in material affluence there is spiritual poverty. We really face spiritual death unless we undertake a radical revolution of values. [We need] to recognize therefore that revolution may be challenging, it may be difficult, but it’s not bloody; it’s a recovery.

JS: What would you like your legacy to be?

GLB: I don’t know. I have to decide how much I am useful and how much I ought to get out of the way. When you get to my age that’s a question that you face. My husband and I saw opportunity in devastation. We saw alternatives and we were ready to create a new American dream.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.

Comments

Very thoughtful and inspiring. Thanks for sharing this piece Jonathan!