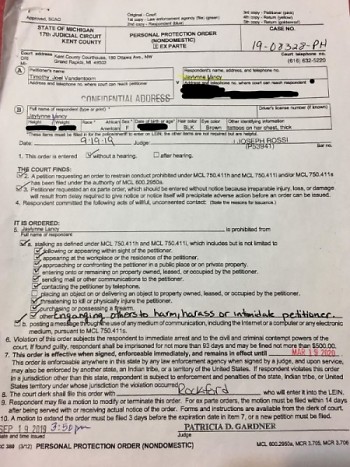

In early September, Jaylynne Yancy filled out a rental application for a unit belonging to United Properties. After a series of negative reviews, public responses, and social media posts described in part one of this article, employees at United Properties had Yancy served with a restraining order (PPO - personal protection order) at her workplace. Read about her experiences in Part 1 of this piece.

Structural racism, classism, and their consequences

Before the PPO, this was a story about some United Properties’ staff being thin-skinned about a negative review and being disrespectful and indiscreet in their public communications with a rejected applicant. The unprofessional response by United Properties and the requirement that Yancy remove the first negative review - in which the biggest complaint was that the website was “misleading” about the time of completing background checks - in order to get her money back is a response already rooted in power and control.

But now, as LaDonna Norman, a volunteer organizer of Together We Are Safe points out, the restraining order will go on Yancy’s criminal record, making her situation even more difficult in the future when it comes to jobs and rentals. (Together We Are Safe is a group that started in the MLK park area that works toward community solutions in a gentrifying city.) Instead of a conflict between two individuals, this is an example of property management company with structural power: United Properties holds the upper hand here, and has harmed Yancy further by adding a PPO to her record. In this case, United Properties has aligned with a judge to hold the power to harm Yancey's chances for future employment and housing.

Though it is incredibly unpleasant to read negative comments about yourself on social media, and it is hard to gauge what people on social media will actually do when they threaten to slap or sexually harm, Norman says that for United Properties to pin a group's comments on one person in a way that will harm her future, while using her financial situation to manipulate her freedom of speech, just isn’t right.

CEO of United Properties, Tim VandenToorn, communicated with Norman via message that United Properties is "not the bad guy here" and that they work with several area charities to try to house those who are housing insecure.

But both Yancy and Norman feel United Properties have taken a simple occurence - a negative Google review - and blown it up by acting out of a racist trope called “the angry Black woman.” This is a common trope in American society that portrays Black women as sassy, ill-mannered, and ill-tempered by nature. Using this trope, whether intentionally or not, the staff at United Properties have confused Yancy’s right to free speech - including posting a negative review - with threatening behavior. Through the "angry Black woman" trope, though Yancy was clearly treated with disrespect in at least some of the company’s communications, and though it is Yancy who was experiencing housing insecurity, Yancy and her community are portrayed as powerful, scary, and irrational - instead of being portrayed as human beings facing the fear and powerlessness of housing insecurity.

In fact, Norman says that Yancy in particular, though she herself said nothing violent, is seen as so scary that one of the co-owners feels he might have to bring a weapon to work, which, whether intentionally or not, evokes another common trope of white supremacy culture: "that we have to be afraid of Black people. It's all a matter of perception."

Meanwhile United Properties is portrayed as the victim, first because VandenToorn said their business suffered from some bad reviews, and then because two or three people other than Yancy wrote out their frustration in a way that could have been venting steam or could have been perceived as a physical threat.

Yancy has rights: the right to name her own experience, the right to warn others who might be harmed the way she was, the right to invite others to speak up if they have had negative experiences, the right to organize, vent, and complain with her friends on her own social media, and the right to face the consequences of her own actions and not the actions of others. In this case, it seems those rights are not being upheld.

The PPO was signed by Judge Patricia Gardner and filed with the Law Enforcement Information Network in Rockford, a richer and whiter bedroom community outside of Grand Rapids, though the United Properties office that Yancy dealt with is not based out of Rockford, which Norman finds confusing.

“Not one of the addresses involved - not the office where these employees feel scared, the rental unit, not her [Yancy’s] address - is in Rockford.” Yet it is in Rockford, a community where people move specifically to remove themselves from BIPOC neighbors and “urban” threats, that Norman says that Black culture and community is often misunderstood and “othered” to be seen as frightening to white people.

Scenes from the housing crisis

Yancy's story is just one small example of the constant human toll of a housing crisis and the imbalance of power it creates. Other renters besides Yancy have other stories to share about property managers and owners other than United Properties. In one recent story brought to Together We Are Safe, a single mother who had her child caregiver in at 5:00 am everyday so she could go to work was being evicted based on having an unregistered occupant - even though the child caregiver had another registered address. Attempts at mediation were rebuffed by the property manager. Again, in this case, the renter and her four children are being put at risk because of a comment by another person, a mover who mistakenly tried to open her neighbor’s door when she first moved in and behaved poorly upon realizing his mistake, scaring the neighbor.

While the cities in the area including Grand Rapids continue to have low rental vacancy rates, the city governments continue to support developers and landlords as the “solution” to the housing crisis. Over the last seven years renters have watched rent prices skyrocket out of their grasp (the average rent for a two-bedroom has gone from $641 in February of 2012 to $1083 in April of 2019, fluctuating wildly along the way). The average rent increase is about 69%, while the area's median household income increase has been 13%. This means renters constantly face the possibility of eviction and unpaid balances, the exact thing that can stop them from qualifying to rent another place in the future.

There are multiple stories of families living in cars or moving out of state. In a place as segregated and rapidly gentrifying as the Greater Grand Rapids Area, this means real harm is being done everyday to women, children, and families of color.

It will not stop until the community comes together to support, not landlords and property owners, but renters, families, and individuals. It will not stop until landlords are held accountable for their participation in structural systems that oppress - not just for following the letter of the law regarding application fees and processes, but for interrogating their place within power structures that make a city like Rockford so different from Grand Rapids.

It will remain to be seen whether community groups like Norman's Together We Are Safe and others will be successful in bringing renters and their allies together to achieve housing justice, and what that fight will look like. Until then, Yancy and thousands of others remain at risk from the power structures in the very city they would like to call home.

Amy Carpenter is a volunteer co-organizer with Together We Are Safe.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.