Two important equity meetings happened in downtown Grand Rapids on Thursday morning.

Equity issues in development

At City Hall, a panel of experts presented their findings on equity - or the lack of it - in the use of public land and incentives in new development. Members of the Rose Center for Public Leadership in Land Use based their recommendations on over sixty interviews they’ve conducted as they studied Grand Rapids.

The presentation was made with big businesses and developers in mind. Presenters pointed out that creating equity means creating income - when all populations are working, earning, and buying, the economy as a whole benefits.

Barriers

The team identified several barriers to equity in Grand Rapids, with recommendations on overcoming them. Here are some that I noted. (Full notes will be at downtowngr.org soon.)

-

There are not clearly defined and measurable equity goals and agendas in place. This results in limited alignment with equity in city policies and incentives such as tax credits to developers. Equity priorities need to be translated to measurable actions in budgets.

-

Developers sometimes believe it’s someone else’s job to promote equity. Since they often work with public lands and tax credits that are public monies, it is up to our elected representatives to hold developers to equity standards.

-

Some developers think that tax credits are always needed to complete their projects, and that they are entitled to those tax credits. City decision-makers must question that and save incentives for those projects that will promote equity.

-

Mobility, parking, and transportation are a real problem in Grand Rapids. People are not currently able to access work, education, parks, or affordable healthy food and other shopping needs because of transit problems. The long travel times on The Rapid in particular were mentioned as a barrier.

-

There needs to be more pro-active attention to equitable workforce development: education, training, mentorship, and networking. If a developer will be asked to use local minority electricians on a project in order to qualify for incentives, then the city needs to work with organizations to make sure those electricians will be recruited and trained in time. This is a particular challenge in a city that has up to 52 percent unemployment in some of its neighborhoods of color.

-

The workforce development process needs to include Human Resources professionals talking to those involved in development, mobility, and other parts of the equity strategy. The city needs to focus, not just on construction jobs, but all sorts of jobs that people want to do and that offer a living wage.

-

Our city officials are risk averse. They are afraid to make mistakes, and often follow conservative legal advice to make sure they’re doing everything right. When it comes to equity and breaking through systemic barriers, we need to support our representatives as they learn to take measured risks on our behalf.

-

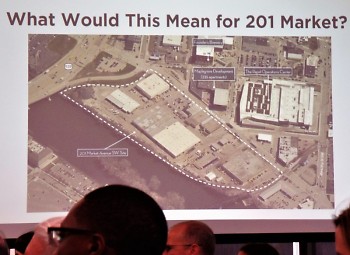

The new development planned at 201 Market Avenue is an opportunity for immediate tweaking of incentives and public input as the city figures out how to incorporate equity goals into its process.

-

There is a lack of trust in the community. Among the public, there has not been enough engagement and conversation, including an underdeveloped communication with neighborhoods.

Trust

“There’s always lack of trust in every city, and there’s lack of trust here [in Grand Rapids] as well. There’s a lack of trust among the community grassroots, maybe they haven’t been a participant in the decisions,” said Antonio Fiol-Silva of SITIO Architecture + Urbanism.

The presenters focused particularly on the need for community engagement, which they warned would be messy and uncomfortable. The team offered that community engagement meetings should offer meals, childcare, and transportation to make it easier for residents to give their time.

In fact, while the presentation focused for fifteen minutes or more on the importance of community engagement, some in the audience noted afterward that they had only found out about the public presentation itself an hour or less before the meeting. Some neighborhood associations had not been notified or included in the study, though various development projects are poised to affect many neighborhoods in the city.

The presenters did note that Grand Rapids does not have a very developed “neighborhood capacity” or communication. The engagement around this very meeting seemed to be an example of that, and an area to work on.

City and county meetings

While the Rose Center presented in City Hall, next door at the County Building the Kent County Board of Commissioners met. The new Diversity and Inclusion plan was unveiled. According to Peter TeWinkle, who attended the meeting, “New county policies will be focusing on leadership, organizational culture (including cultural intelligence training), and accountability with new performance measures.” TeWinkle notes that the county workforce generally reflects the demographics of the county, except in representation of the Hispanic community and, very importantly, at the leadership level.

The fact that the meetings took place at the same time, - with some confusion in public notice - and that both meetings were during the business day when much of the public is not available - all of these factors meant that many area residents who need equity the most could not attend one meeting, much less both. It seems to be a continuing problem with communication among different agencies and with the public.

Will we say no to prioritize equity?

My question, which I asked during the Rose Center meeting, is this: Some of West Michigan’s big money donors and decision-makers have historically not been on the side of equity. Some donors will not support, say, mental health issues, and some are not for LGBTQ issues. So how do we, the public, have trust? What I would like to see is that our city will sometimes say no to big money if it means leaving people behind.

The experts on the Rose Center team had various answers. They offered that trust is not a destination but a journey, including the conversation to look at different dimensions of equity. They offered that we need to create a process for creating trust that includes discussing our history, including past bias and disinvesting in certain communities. They offered that we need to ask in a positive way for consistent measurable actions. In particular, Cristina Garmendia of Rutgers University said, “In Grand Rapids [leadership], there has been a culture of yes - [saying yes to projects] for fear of losing out or making the wrong decision. I will take Grand Rapids seriously when they have said no to a project based on prioritizing equity.”

I agree. I hope for a day when we, the residents of West Michigan, commit to working with and caring for all our people, including those in marginalized and stigmatized groups -- even if it means saying no to new buildings and special projects that put us on a top 20 list. I am more interested in us learning to show up for each other, even if it is in a shabbier building and with a simple purpose.

As my series on the Faces of the Housing Crisis concludes, I have spent time with five wonderful and marginalized people who have experienced the stress of housing insecurity for themselves or those they care about. In other work, I have spent time learning about and valuing the contribution that undocumented immigrants make to our community. With their stories in mind, I truly hope for the day when we admit our biases and intentionally shift our power into the hands of the vulnerable. That may be the day that we, just as we are, are enough.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.