Step out of the frenzy of ArtPrize and into the "slow art" of Makoto Fujimura.

ArtPrize is an amazing experience, but it can become an all-you-can-see visual cacophony. In loving the art we can work ourselves into a state that is effectively drive-by arting. There's so much art that the ArtPrize marathon can become a daily sprint to see it all. But in capturing as many sights of art as we can, it's possible to lose the experience of art itself- the contemplation and enjoyment of the piece before us.

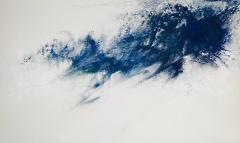

Makoto Fujimura's ArtPrize entry "Walking on Water-Azurite" at the Acton Institute (98 East Fulton Street) invites us back into that experience.

Fujimura practices Nihonga, a Japanese style of painting.

"Nihonga is an art form with a lineage that goes back to the 12th century. I was privileged to be invited to be part of this lineage system at Tokyo University of the Arts, under Matazo Kayama, arguably the greatest Nihonga artist of 20th century. Nihonga uses pulverized minerals with hide glue, making your own paint, [and then] painting on hand made paper or silk. It is a collaborative art, working with artisans and nature to reflect the ecosystem of Japanese aesthetics," says Fujimura.

"The Golden Sea documentary documents the process of Nihonga, with the first 'pour' for this 'Walking on Water' painting captured on film,” he notes.

In contrast to much of the recycled art one sees at ArtPrize, the pulverized minerals Fujimura uses are what he acknowledges to be extravagant materials, including precious metals like gold. For Fujimura, this is a meditation of and grappling with his Christian faith in a God whose love is extravagant.

Considering how different Fujimura's approach is, why did he come to ArtPrize?

"It was by the gracious invitation by Acton Institute to exhibit, and they even created a huge wall for it! I avoid art fairs and art competitions, due to the nature of my art being 'slow art.' Like 'slow food' my art takes a long time to create and also to learn to appreciate. The refractive, prismatic nature of the azurite and malachite on 'Walking on Water' will require that the viewer slowly take in the piece for at least 10 minutes before the eyes adjust to see the prismatic colors," he says. "My work does not fit the 'frenzy' of a quick look. I have described what I do as ‘a combination of Mark Rothko and Fra Angelico.'"

His work is also a combination of his Western and Asian influences. He spent time as a boy in Japan and also lived within three blocks of what became Ground Zero in New York City with his family. Fujimura has responded to 9/11 in his works, and in "Walking on Water - Azurite" he responds to the tsunami tragedy of March 2011.

"Just as I had done after 9/11, in responding to the 'Ground Zero' conditions with my paintings, I simply wanted to push my imagination to see the possibility of 'Walking on Water' to metaphorically move beyond the devastation power of water. The 'Walking on Water' series were painted in the new Princeton studio, all meant as an elegy to the aforementioned 3/11 tsunami. As I attempted to complete the last of the three images, Walking on Water – Banquo’s Dream, Super-storm Sandy hit, wiping out some fifty of works at Dillon Gallery, my New York gallery. Thus the process of painting had become, literally, a way to ‘walk on water,’” he explains in his ArtPrize bio.

What should visitors look for in his art, especially if they are new to Nihonga, or even art itself?

"Art is about questions, rather than answers. I hope people, in taking in my works, notice the paradoxes embedded in the work, such as 'how can a static, 2D image become dynamic, and multi-dimensional?' or 'how can the destructive power of water create stillness?' Even 'how can we imagine 'walking on water,' over the destruction and challenges we face in our lives?' as I hope this particular work can elicit in the viewer," says Fujimura.

ArtPrize visitors should not only take this rare opportunity to see the work of an internationally-lauded master of Nihonga, they should also give themselves an "extravagant" 10 to 20 minutes to rest in front of its beauty.

"Ultimately my work is about flourishing, what T.S. Eliot called 'the still point of the turning world.'"

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.